Rafael Laguna, Director of the Federal Agency for Breakthrough Innovation (SPRIND), made a striking comment in an interview during the annual courtyard festival on September 11, 2025. He said verbatim:

“My parents were translators, just like yours. They’re gone. The job is gone; it simply doesn’t exist anymore. Well, maybe still for literature, but for technical documentation and the like – it’s over. It’s really over.”

A brief note on the first sentence: Rafael and the author are on familiar terms, and indeed, both his and my parents were translators.

Oliver Czulo is a professor of Translation Studies specializing in data-based semantic research and founder of the Institut für Translatologie gGmbH. He is not inclined to let Laguna’s statement stand unchallenged. We met via Zoom for a conversation.

An Experiment

Before we turn to the main discussion, a small experiment.

We asked three AI-based translation systems to render the German title question „Wird das Übersetzen künftig ein reiner Maschinenjob?“ into English.

The results were unexpectedly divergent.

DeepL translated it as: “Will translation become just a job for machines in the future?” – which, when translated back into German by DeepL, reads: “Wird Übersetzen in Zukunft nur noch eine Aufgabe für Maschinen sein?”

ChatGPT rendered it as: “Will translation in the future be purely a machine job?” – which, when back-translated, becomes: “Wird Übersetzung in der Zukunft vollständig von Maschinen übernommen werden?”

The system also offered shorter variants such as “Will translation in the future be done entirely by machines?” and “Will translating in the future be carried out exclusively by machines?”

Google Translate’s version was: “Will translation become a purely machine-based job in the future?” – and when translated back into German: “Wird Übersetzen in Zukunft eine rein maschinelle Tätigkeit sein?”

A simple question – and three programs provide differing answers, though all are, in some sense, semantically correct. Notably, two of the three avoid the term „machine job“.

For the author, this raises several questions:

Do we need to adapt our language to AI in order to achieve consistent translations across different systems?

Can AI truly render everything meaningfully into other languages, or do we still need human translators?

Professor Czulo, Mr. Laguna’s statement is quite sweeping and aligns with the notion of disruptive technologies. How do you view it?

With the term disruption you’ve touched on something essential, and I’d like to start there.

Hovering above such statements is the spirit of Silicon Valley – a mindset encapsulated in slogans like “move fast and break things.” Behind it stands a digital industry that has indeed had its successes and has transformed many aspects of life. But there remains this yearning for another iPhone moment – the kind of turning point Apple achieved in 2007, when it unveiled the iPhone, swept competitors from the market, and fundamentally changed how we interact with one another.

Today, the tech sector has matured; it is, in the best sense, an established industry with its services and products. Yet many within it cannot let go of that early disruptive spirit. Figures like Zuckerberg and Musk, once the rebellious innovators, seem unable to accept that they are no longer the young mavericks. Over the past years, we have heard many grand promises: Uber, for instance, wanted to revolutionize transportation but has effectively become a taxi brokerage company. Airbnb facilitates vacation rentals, yet hotels still exist – no revolution there either.

Now the focus for several years has shifted to translators. For an industry driven by the impulse to “break things,” it would be considered a major triumph – regrettably – to bring an entire profession to its knees. Of course, such goals are announced with great pathos: the ambition to change the world, to improve it, to tear down language barriers. Statements like Mr. Laguna’s, I believe, originate in that narrative. But as history shows, many of these grand announcements have often landed with a thud.

When I look at the examples mentioned in the introduction, one thing comes to mind: In German, the term Dolmetscher corresponds to interpreter in English. Does AI sometimes interpret more than we intend it to?

What we call AI is, in essence, complex statistics. It searches existing data for recurring translation patterns. That can sometimes lead to rather peculiar effects. Let me give you my favorite example: the “Wohnberechtigungsschein” (certificate of eligibility for social housing). This example reveals several issues that I have been discussing for more than a year now. I have observed how different translation tools handle it over time.

Google Translate still renders it as residence permit, as if it were a document granting general permission to reside somewhere. The problem is that there is no fixed English equivalent for this German term. The statistical system tries to approximate a translation based on contextual probabilities. It produces a result that may sound close but conveys a completely different meaning.

DeepL, interestingly, has changed over time. It now offers several variants, one of which is still residence permit. The currently preferred version, however, matches the translation used on the City of Leipzig’s official website: roughly, certificate of entitlement to social housing. That points to another recurring problem in translation work.

The first issue lies in the source text itself – both texts and the terms therein are often vague, ambiguous, inaccurate, or stylistically weak. What does “Wohnberechtigungsschein” even mean? If I don’t know, I might make all sorts of assumptions. Proper linguistic work would begin by asking: could we perhaps find a clearer German expression so that citizens understand it better?

The task of translators and interpreters remains to identify an interpretation – precisely as you said – that actually reaches the intended audience. AI does not do that.

Let me give another example. On Saturdays, we occasionally watch those home renovation shows – you’ve done your shopping, you’ve cleaned up, and now you sit down with a coffee to relax. The German version uses voice-over dubbing, so you still hear the English original faintly underneath. I recall a scene where someone walks into a newly renovated house and keeps exclaiming “Awesome, awesome, awesome!” into the microphone.

That’s not how we communicate, and it’s not how I respond either. Most German viewers would find it excessive. The German overdub translated it roughly as “This room looks completely different now.” That is a German way of expressing praise! An AI would probably have produced “Toll, toll, toll” (“great, great, great”), which simply doesn’t fit our communicative norms.

This is part of human competence: deciding how to interpret and then how to render something appropriately.

Mr. Laguna suggested that human translators may still be needed for literature. But as journalists, even though we are not novelists, we often try to amplify meaning linguistically – as with the phrase “machine job,” which conveys nuance the AI may not catch. Is this simply a matter of technological progress?

Mr. Laguna himself pointed out in the interview that the systems currently in use are all built on essentially the same technological foundation. From that perspective, I don’t see a substantial improvement coming anytime soon, despite all the promises. And to be frank: I think even the engineers themselves are smart enough to know that.

I recently attended a conference session where AI was discussed as a mediation tool in hospitals. Several companies presented their products. Even the simplest translation examples shown raised questions. Repeatedly, audience members asked: “What about liability? Who is responsible if a translation error occurs?” The room fell silent. Eventually someone replied, “Well, a one-hundred-percent accurate translation cannot always be guaranteed.” Naturally, these companies will disclaim liability and insist that a human must make the final judgment about whether an output is usable or not.

I therefore do not foresee major change, but I do see another danger – on several levels, including for the AI industry itself. The current success of the AI sector rests on extraordinarily favorable initial conditions.

We already have several decades of digitization behind us. The internet holds vast amounts of data, much of which certain companies have simply taken – let’s say, without asking.

We know this from the visual arts: graphic designers have brought lawsuits because their works were used for training image generators without consent or payment.

The same applies to translation systems. Many of the translations available online were created over decades by humans – often by highly trained professionals producing high-quality data. These were then used to train systems that could be monetized.

Now, what happens if we claim that translators and interpreters will no longer be needed? Translators are not data suppliers per se, but from the AI industry’s perspective, this raises a real problem. Language constantly evolves. A translation system performs well only if it has rich training data for the relevant subject matter.

Who will produce such data in the future, if public discourse – already visible today – discourages students from entering the field because they believe, “Translation and interpreting are no longer worthwhile”?

The AI industry is, quite literally, sawing off the branch it sits on. I believe some within the field have realized this, but unfortunately that awareness is still missing from public communication.

So it’s more a matter of promoting a business model than reflecting the actual technological reality – if we put it politely?

Politely put, yes. I would welcome a real dialogue with those responsible. What is missing, I think, is someone from the AI industry with broad public reach standing up to say clearly: Of course we still need human interpreters and translators.

Let’s return to Mr. Laguna – he heads the Agency for Breakthrough Innovation, which exists to strengthen Germany as an economic location. Germany is home to people of diverse backgrounds, surrounded by more neighboring countries than any other in Europe, and its economy depends heavily on exports.

Statements like the one in that video, which are echoed in politics, create a climate in which we begin to unlearn essential competencies.

For example, Minister-President Kretschmann proposed abolishing the requirement for a second foreign language in Baden-Württemberg schools. Measures like that make our country culturally, economically, and technologically poorer. And that, in my view, is a serious problem on the horizon.

You’ve just mentioned something I personally find troubling about AI – the problem of de-skilling. As convenient as it is to use a phone app to ask for directions to the train station in China, do we risk losing the ability to handle other languages if we rely on such tools too much?

We are already seeing this on a broad scale. Programmers are complaining that entry-level jobs are disappearing because people assume machines can do them better. But who will become the experienced senior programmers capable of solving the really complex problems later on?

Regarding your example of smartphone translation tools: yes, the digital industry has achieved remarkable progress, and that’s great. In certain low-risk situations – on vacation, or when visiting someone in the hospital – having an app that provides basic information is genuinely helpful.

But the problem of forgetting skills, which we already touched on, raises a deeper question. I think what’s becoming increasingly pressing is the issue of our overall language strategy – in schools, in government, and nationally.

Most federal ministries in Germany have translation departments. The Bundeswehr has its own Federal Office of Languages. In courts and hospitals, translation and interpreting occur daily. Yet these processes are often improvised rather than systematically organized. What we lack – and what the European Union, for instance, does have – is a consistent national language strategy.

If we want to ensure that we don’t lose linguistic competence, we must think comprehensively about how to support language and cultural mediation throughout society.

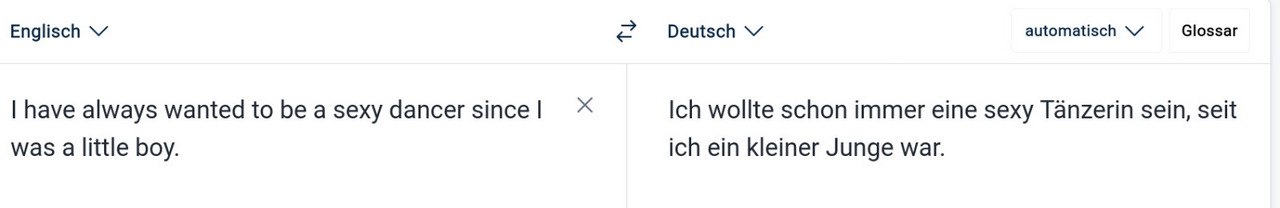

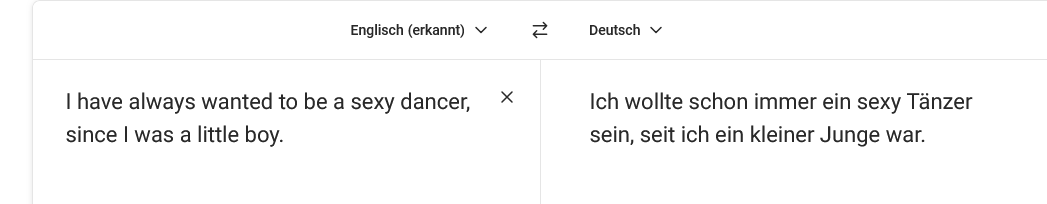

In our first interview, you criticized that machines have no understanding of gender or stereotypes. I repeated those tests; the systems have improved. For example, in the “sexy dancer” case, the AI now recognizes gender – though inconsistencies remain. Is that issue resolved?

I’ve tested it periodically myself. Some examples that failed early on now work. But new examples fail again, because – contrary to the popular metaphor – the program doesn’t actually understand anything.

It needs enormous amounts of training data to adjust its statistical patterns so that it stops reproducing certain stereotypes. That process is extremely costly.

To return to your question – will it just get better over time? Mr. Laguna himself admitted that a completely new algorithm would be required. And that algorithm is supposedly always “just around the corner.”

What people overlook is how much development and money would be needed. To give you a sense of scale: OpenAI reported a loss of about 13 billion USD in the first half of this year alone.

We tend to imagine only a few programmers at work, but in truth, the “I” in AI – intelligence – comes from human expertise: translators, interpreters, graphic designers, lawyers, and many others whose highly qualified work provides the data for training these systems.

Yet we still have no method to teach machines what our world actually is – what gender or origin mean.

A machine doesn’t even understand what a computer is; it has no conception of such things.

We are entering a phase reminiscent of the 2000s, when researchers tried to combine rule-based systems – structured world models – with statistical methods. That works to a limited extent, but we still don’t have a machine that truly understands the world or possesses lived experience.

Interestingly, Mr. Laguna raised a similar criticism – he noted that some definitions of intelligence used to describe AI as “intelligent” are themselves questionable.

So your conclusion would be: translators and interpreters will continue to exist, though the profession will evolve?

Let me briefly address that point: “Yes, the profession is changing.“ Since the late 1990s, the field has undergone continuous digital transformation. Current reports describe this evolution differently – some are pessimistic market analyses, others are more optimistic graduate surveys. One new trend is that more professionals are moving into salaried employment rather than freelancing. Companies are bringing back in-house tasks that used to be outsourced. Freelancers, however, are struggling – largely due to the price pressure clients exert by pointing to AI as a cheaper alternative.

At the same time, entirely new workflows are emerging, especially in technical and medical communication, which now rely heavily on digital mediation. These areas, too, require creativity – not only literary translation.

Overall, it’s a development that defies easy prediction and, at times, causes genuine concern.

But one thing is absolutely clear: we still need human expertise. We need students, graduates, and active dialogue with the AI industry.

I think some key insights haven’t yet sunk in. And if I may end with a proposal: perhaps it’s time to move away from the Silicon Valley mantra “move fast and break things.” What about “innovate and improve” instead? That would mean think anew and make better.

For that, we need dialogue – and I would very much like to invite Mr. Laguna to such a conversation.

A fitting closing statement, Professor Czulo. Thank you for the interview.

Empfohlen auf LZ

So können Sie die Berichterstattung der Leipziger Zeitung unterstützen:

There is one comment